- Home

- FUN & Forums

- Vintage 3d Photos

Vintage 3D Photos

You will find a collection of vintage 3D photos enhancing various pages throughout this vintage-themed website. Some old fashioned images are in the double-picture Stereograph format which you can view without the need for special glasses.

The more modern images are in the Anaglyph 3D format, and you'll need special 3D glasses to view them. All the vintage 3D images are remarkable to look at. Have fun viewing!

Anaglyph 3D

Experience the 1950s with 3D Photographs and Drawings

Experience the 1950s with 3D Photographs and Drawings(Source: ©KateKlimenko/Depositphotos.com)

The 1950s saw a 3D craze where movies, photographs, and even comic books were presented in startling 3D depth during the few years the fad lasted. However, people have been fascinated by anaglyph 3D images since the late 1800s.

How Does Anaglyph 3D Work?

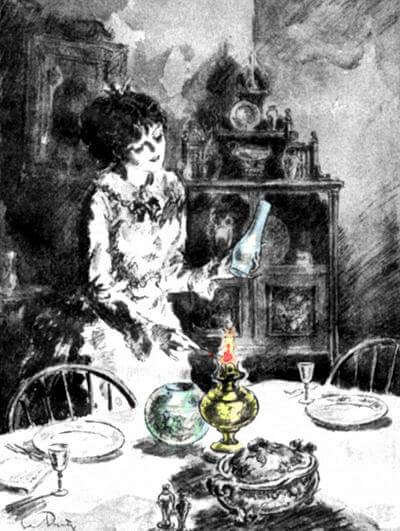

3D Anaglyph Picture of a Lady Looking into a Stereoscope

3D Anaglyph Picture of a Lady Looking into a Stereoscope(Source: Dave Pape [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Anaglyph drawings utilize a two-color printing process, and a two-color viewer consisting of special glasses with relevant colored lenses. The same picture is printed first with a red ink and then with a greenish-blue ink.

Your left eye looks through a red lens that filters out the red lines, so it only sees the greenish-blue lines on the picture. Simultaneously, your right eye looks through a greenish-blue lens that filters out the greenish-blue lines, so it sees only the red lines on the picture. Your brain combines the two pictures into one image giving the illusion of depth.

Anaglyph photos and anaglyph movies follow a similar color process. Cameras with two tinted lenses are used, each lens filming from a slightly different position relative to the distance your eyes are apart.

The processed pictures appear blurred when viewed with the naked eye, but they become clear and three-dimensional when viewed with the necessary 3D glasses.

Anaglyph 3D Photographs

How to View Anaglyph 3D Images on a Computer

How to View Anaglyph 3D Images on a Computer(Source: ©luna123/Depositphotos.com)

3D glasses are needed to properly view the anaglyph 3D photos on your computer screen.

Plastic or card stock glasses with red-blue lenses can be purchased very cheaply from Amazon online, or you can even make DIY 3D glasses as demonstrated in the short YouTube video below.

The following anaglyph 3D photographs are featured on pages of this site:

Harbor in Portofino in Liguria, Italy

Olvera in Cadiz, Andalusia, Spain

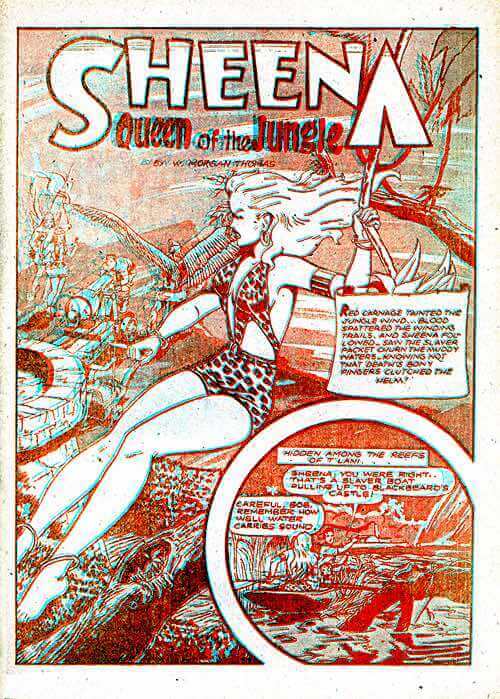

Anaglyph 3D Comic Books

There were approximately fifty 3D comic book titles published during the 3D craze of the early 1950s. Aside from the familiar characters of Mighty Mouse, the Three Stooges, Superman, and Batman, there arose new characters such as Captain 3D and the popular Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.

Sheena, Queen of the Jungle 3D Comic Book

Sheena, Queen of the Jungle 3D Comic Book(PD Source: Fiction House Magazines, 1953)

Hand-drawn comics with their distinctive 3D effect first appeared on newsstands in 1953. Sadly, their spectacular beginning ended just one year later in 1954, as the novelty of 3D comics rapidly diminished.

As with the recent demise of 3D television, the inconvenience of wearing 3D glasses had much to do with the demise of 3D comics. The glasses were a card stock insert in the comic, and their flimsy nature, and colored cellophane lenses could not withstand rough handling. Once the glasses were damaged, the comic book became unreadable.

What's more, unless you took the trouble to attach a string or an elastic to your red-blue glasses, you had to hold them steady to your eyes while reading, and it soon became all too tiring for most young readers.

Some publishers cleverly developed their own patented techniques to produce the 3D panels with a greater illusion of depth and motion, and the higher costs for the 3D drawings resulted in a newsstand price of 25 cents compared to the 10 cents charged for standard comics. It was more than a child's allowance could bear.

Publishers caught up in the 3D comic craze included St. John Publishing Company, National Comics, Stereographic Publications, Atlas, Harvey Famous Name Comics, and E. C. Comics.

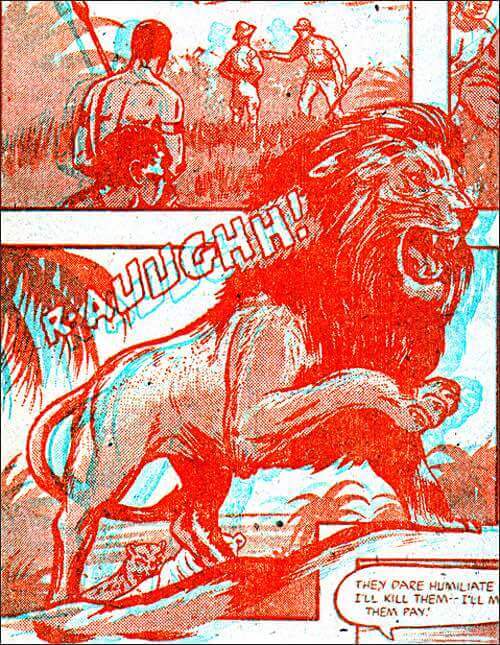

Sample Frame from 3D Comic Book

Sample Frame from 3D Comic Book(PD Source: Fiction House Magazines, 1953)

This enlarged sample frame from "Sheena, Queen of the Jungle" offers an excellent example of the anaglyph graphics featured in 3D comic books from the early 1950s.

Put on your red-blue 3D glasses and note how the lion appears to leap off the page as the scenery recedes into the background. Note how greater depth and motion can be simulated as you move your head from side to side. The 3D comics were truly a visual novelty.

Thankfully, all is not lost. The Digital Comic Museum is one of the best sites to view and to download digitized 3D comics from the early 1950s.

Anaglyph 3D Movies

Watching Anaglyph Movie With 3D Glasses

Watching Anaglyph Movie With 3D Glasses(Source: ©TerasMalyarevich/Depositphotos.com)

Want to see a great example of an anaglyph 3D movie? Here's a YouTube trailer for "Creature from the Black Lagoon," a 1954 black-and-white 3D monster film starring Richard Carlson, Julia Adams, and the famous Gill-man creature.

Creature From the Back Lagoon has been digitally remastered and released in 4K and Blu ray by Universal Pictures in both 3D and 2D versions for comfortable home viewing.

3D Stereograph Pictures

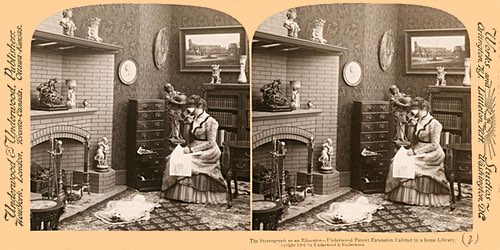

Antique Stereograph of a Woman Looking into a Stereoscope

Antique Stereograph of a Woman Looking into a Stereoscope(Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., LC-DIG-ppmsca-08781)

Stereoscopic 3D photos (also called stereographs) came into demand after the stereoscope was invented by Mr. Elliot of Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1839. A British scientist and photography pioneer, David Brewster added glass lenses to improve Elliot's design, and his "lenticular stereoscope" became the first portable 3D viewer.

Brewster's Stereoscope was demonstrated at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and demand for stereographs exploded soon after. Stereographers traveled the world to photograph well-known attractions to meet public demand for the now-popular "stereo cards."

Stereoscopes became popular in America during the 1860s when stereographs of Civil War battle scenes were in big demand. By the early 1900s and the First World War, stereoscopes were one of the most popular entertainment devices found in homes across North America.

Today's View-Master® and Google Cardboard™ owe their origin to the old fashioned stereoscope.

How Does a Stereoscope Work?

A stereoscopic 3D camera attempts to mimic human vision by taking two photographs at once and offsetting them by a small distance relative to the distance your eyes are apart, about 2 1/2 inches. The left photograph corresponds to your left eye and the right photograph corresponds to your right eye.

When the paired photos are viewed in a stereoscope, your left eye sees only the left image and your right eye sees only the right image. Your brain combines the two images into one giving the illusion of depth or what became known as 3D in the 1950s.

It is possible to view stereoscopic photos without a special viewer simply by leaning in close and staring through the photos while slightly crossing the eyes until the two photos converge to form one central 3D image.

It can take a minute or two for the image to materialize, and some people find this "cross-eyed" method easier to do than others, but it is fun to try.

View Vintage 3D Stereographs

The following stereographs are featured on pages of this site:

Young Children Singing Christmas Carols, circa 1890

Children Play Ring Around the Rosie, Christmas Day, circa 1897

Easter Eggs on Easter Morning in the White House, circa 1904

Cataract House Hotel, Niagara Falls, N.Y., circa 1900

Young Couple in Their Kitchen Cooking Supper, circa 1903

"Y Girls" Making Doughnuts on the Rhine, circa 1914-18

1909 World's Fair, St. Louis, Missouri

Victoria, Queen and Empress, circa 1901

Thanksgiving Dinner Table, circa 1923

Hotel St Francis, San Francisco, circa1911

The Waldorf Astoria on Fifth Avenue, NYC in 1903

The Coronet 3-D Camera

Coronet 3-D Camera with Binocular Viewfinder circa 1955

Coronet 3-D Camera with Binocular Viewfinder circa 1955(Source: ©Don Bell)

Are you old enough to remember the Coronet 3-D camera? It was a low-cost camera cleverly designed to take black and white stereoscopic photographs (stereographs) that could be viewed in 3D simulated depth.

Made by the Coronet Camera Company in Birmingham, England, the novel camera took advantage of the 3D craze during the mid 1950s.

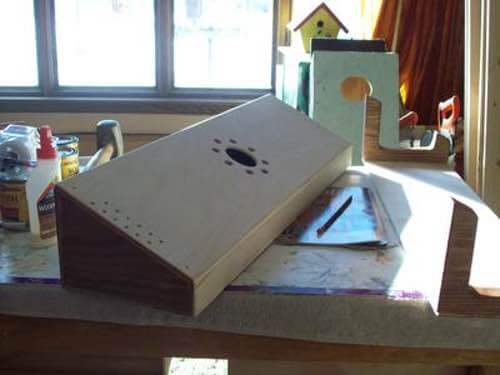

Back of a Coronet 3-D Camera with Operating Instructions

Back of a Coronet 3-D Camera with Operating Instructions(Source: ©Don Bell)

The Coronet 3-D camera wasn't pretty to look at. It was somewhat clunky in its appearance and simple in its design, yet it proved practical for taking vintage-style 3D stereographs with its binocular-type viewfinder.

The camera used standard No. 127 black and white roll film, but instead of the usual eight photos per roll, it took four pairs of photos, making four stereographs.

Coronet 3-D Camera Controls

Coronet 3-D Camera Controls(Source: ©Don Bell)

The unique camera could be set to take regular 2D photos simply by turning a small knob next to the right-hand lens which simply rotated a metal disk called a cover blade to block light from entering the one lens.

Blocking the light permitted the left-hand lens to take eight photos similar to a standard 2D camera.

The only other controls included a large knob to advance the film roll, a sliding lever to preset the shutter spring, and a metal shutter release button. Photos could be taken indoors by purchasing an optional flash unit and a supply of flash bulbs.

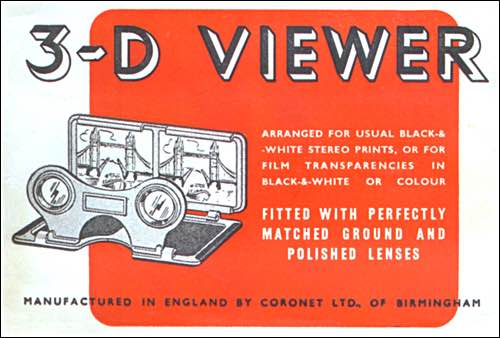

Coronet 3-D Viewer for Viewing Stereo Prints

Coronet 3-D Viewer for Viewing Stereo Prints(Source: ©Don Bell)

One major drawback was the need for custom film developing. Local photo finishing labs were not equipped for printing the negatives in pairs. The prints needed to be trimmed to a proper 1-3/4-inch size to fit the 3D viewer and transposed to get the full 3D stereoscopic effect.

For instance, the pair of photographs must be developed and meticulously cut down the center, with the right-hand photo positioned to be viewed in the left-hand side of the viewer and vice versa. The photographs were printed to maintain this position permanently.

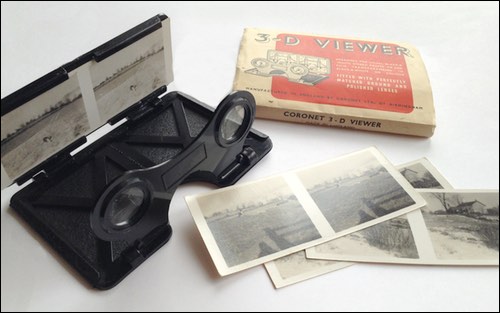

Coronet 3-D Viewer and Stereo Prints, c.1955

Coronet 3-D Viewer and Stereo Prints, c.1955(Source: ©Don Bell)

North American owners of the Coronet camera had only three photo labs equipped to develop and print pictures to specifications: one in New York, one in Hollywood, and one in Toronto, Canada.

Single rolls were processed for 60 cents or two rolls for $1 in 1955, corresponding to $9.29 US in today's dollars for four 3D-stereo pairs of pictures.

I can remember purchasing my Coronet 3-D camera at the Woolworth store in Peterborough, Ontario. They were on sale for $2.95 at the time which would amount to around $28 CDN in today's money, allowing inflation.

That 3D camera was a major purchase for a 9-year-old farm boy without an allowance in 1955, but I was intent on having it and worked throughout summer to pay for it.

Disappointingly, the reality of its costly film processing resulted in me taking just a handful of 3D photos, three of which I've digitized and display below.

Stereo Print of Cat Trixie Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera

Stereo Print of Cat Trixie Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera(Source: ©Don Bell)

Stereo Print of Dog Barney Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera

Stereo Print of Dog Barney Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera(Source: ©Don Bell)

Stereo Print of a Stone House Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera

Stereo Print of a Stone House Taken by a Coronet 3D Camera(Source: ©Don Bell)

The old-time stereograph picture creates a 3D effect. View it by crossing your eyes slightly until the two images merge into one central 3D picture. It's a fun visual trick to try.

How to Create 3D Photos

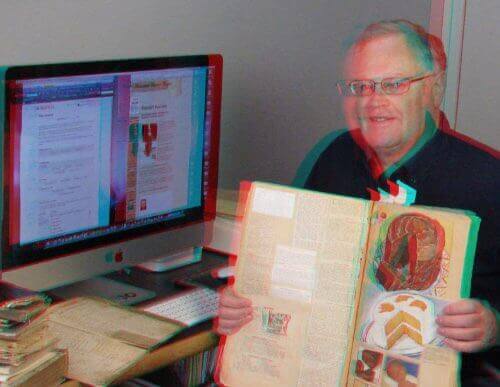

3D Anaglyph Photo of Don Bell from IMGonline

3D Anaglyph Photo of Don Bell from IMGonline(Source: ©Don Bell)

If you would like to try creating your own 3D photos, IMGonline offers a FREE online tool that will easily convert almost any digital photo from 2D to 3D.

Convert your photo to either a red-blue anaglyph image or create a two-picture stereoscopic image. Take your choice. Enjoy!

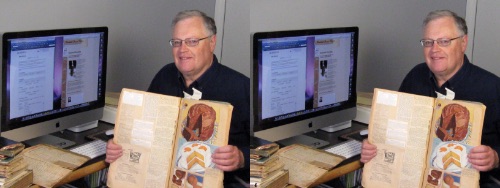

Stereoscopic 3D Photo of Don Bell from IMGonline

Stereoscopic 3D Photo of Don Bell from IMGonline(Source: ©Don Bell)

Your image results will vary depending on the quality of the photo you upload, but you will find your 3D image conversion interesting if not downright impressive.