- Home

- Ice Cream Recipes

- Ice Cream History

Ice Cream History

Explore this fascinating overview of ice cream history, and you will discover how ice cream evolved from ancient times and how it has become part of our everyday culture.

Ice Cream History

© 2004 by Don Bell

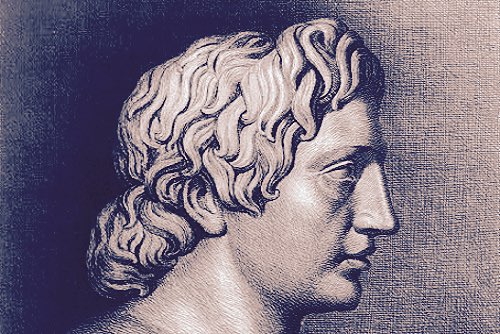

Soda Jerk Flipping Ice Cream Ball Into Milk Shake

Soda Jerk Flipping Ice Cream Ball Into Milk Shake(PD Source: Library of Congress LC-USF34-0322640D)

The Ancient Era In Ice Cream History

The exact origin of ice cream is not known and much that has been written on the subject is either theory or the distillate of legends.

That said, many believe that the early Greeks enjoyed a mixture of snow and fruit juices packed into goblets.

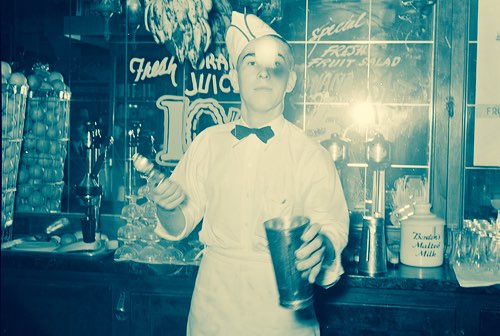

Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.) was known to be extremely fond of frozen beverages; hence, the dessert named "Macèdoine."

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great(PD Source: Library of Congress LC-USZ62-40088)

To celebrate his conquest of Egypt in 345 B.C., Alexander had deep trenches dug in the earth and filled with snow transported from the mountains for the preparation of frozen beverages.

It is said that he raised his men's spirits before battle with a chilled confection of snow, wine, apple juice, and honey.

As early as 200 B.C., history records the wealthy Romans eating snow flavored with fresh fruits and honey. Emperor Nero (A.D. 37–68) had his slaves transport snow 80 kilometers from the peak of Mount Terminillo, also known as the Montagna di Roma, and used it to make refreshing water ices flavored with fruit juices and ginger, coriander, or cinnamon.

These journeys had to be orchestrated with precision for not only did the relay runners have to return with the snow before it melted, but they had to arrive at the exact time it was needed for the banquet since failure often meant their deaths.

Later, ships would transport ice from Mount Vesuvius and Mount Etna to the major Roman ports to enable the aristocracy to prepare frozen confections. Apparently, Nero had specially insulated rooms built deep beneath the palace to store the frozen cargo.

In China, the period of the T'ang dynasty (A.D. 618–907) is considered by many historians to be the golden age of Chinese civilization.

Preserved Chinese records indicate that in the capital city of Chang'an (now Xian) the T'ang Emperor had the milk from buffaloes, horses, camels, yaks, cows, or goats fermented into yoghurt that was then mixed with rice flour for thickening and lightly flavored with "dragon's eye powder," which was what the Chinese called camphor. Ice was then packed around the mixture to allow it to freeze.

The T'ang Emperor is said to have had about 8 dozen icemen who were responsible for collecting and storing the ice, which had been harvested in the winter and stored in underground ice-houses in China since 1100 B.C.

The T'ang emperors also opened important trade routes to India, the Middle East, and Europe, and some scholars believe that the knowledge of making frozen confections flowed along these ancient trade routes to the West.

The Medieval Era In Ice Cream History

In March 1194 King Richard Coeur de Lion (1157–1199) returned to England from the Third Crusade after a year of imprisonment in Germany.

The story persists that King Richard brought orange and lemon sherbet recipes that had been given to him by the Sultan Saladin (1138–1193).

Sir Walter Scott lends credence to the tale in his nineteenth century novel The Talisman, wherein he refers to "sherbet of the most exquisite quality, cold as snow."

Scott describes the fabulous tent where Saladin welcomed King Richard and the Princes of Christendom amid the richest splendors of the East:

Shawls of Kashmere, embroidery in arabesque, vessels of gold and silver and porcelain, and "large mazers of sherbet cooled in snow, and ice from the caverns of Mount Lebanon." To many Europeans, sherbet epitomized the exotic, mysterious East.

These tales may bear truth for there is strong evidence that milk ices were commonly eaten in parts of central Asia in the twelfth century, and we know that even before the time of the Crusades, water ices were quite popular throughout the Middle East. The words "sorbetto" and "sherbet" are derived from the Arabic sharbat.

The Italian trader Marco Polo (1254–1324) is said to have brought a recipe for sherbet-like desserts to Europe when he returned from the Far East in 1295 bearing tales of eastern kings who ate strange frozen delicacies. Legend or not, frozen ices become popular in Venice and throughout Italy.

The Renaissance Era In Ice Cream History

Eventually, cream was combined in frozen dessert mixtures, but the exact date this occurred remains unknown in the annals of ice cream history.

In October 1533 the 14-year-old Florentine princess Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589) married the future Henry II of France and introduced frozen ice cream to the French court.

Her personal chef, Ruggeri, molded ice creams flavored with raspberry, lemon, cherry, orange, and wild strawberry into miniature monuments that were served at the lavish, month-long wedding banquet. It is said that the delighted guests were surprised with a different ice cream flavor each day.

Having grown tired of the petty jealousies of the court chefs, Ruggeri is reputed to have sent his secret recipe for freezing ices to Catherine in a sealed envelope before leaving Paris for home.

Ruggeri's recipe was kept a strict secret among the court chefs who experimented with molding sumptuous ice creams and water ices. Such desserts became trendy among the French nobility who vied for invitations to the lavish palace banquets.

It is said that Catherine's son, Henry III (1551–1589), became addicted to all manners of ice creams and insisted on eating them daily throughout his short life. The peasants of the realm, however, heard only vague rumors about an unusual frozen confection being served at the palace.

Ice cream production became more practical around the middle of the 1500s with the discovery that salt mixed with ice produces a lower temperature than that of ice alone.

Lower temperatures accelerate the freezing process and produce a smoother, creamier ice cream with fewer ice crystals.

Since the freezing process now took less time, more ice cream could be produced. Some credit the Italian architect Bernardo Buontalenti (1536–1608) with the discovery, but this cannot be verified as many took credit for the progress.

Buontalenti is known to have produced fabulous frozen desserts made with fresh fruit and zabaglione, a fluffy custard-like sauce made with beaten egg yolks, sugar, and wine.

The Stuart Era In Ice Cream History

The English might have learned how to make ice cream around the same time as the French or possibly even sooner; we can never know for certain.

We do know that ice cream, or "crême ice" as it was called, was served regularly as a delicacy at the table of James I (1566–1625) and that it was very popular with all the Stuart monarchs.

This was a time of lavish royal banquets with elaborate desserts and sweetmeats. A life-sized pastry deer was served which bled red wine when arrows were removed from its sides on one occasion at Windsor Castle.

It has been alleged that Charles I (1600–1649), the son and successor of James I, once hired a French chef named de Mirco to make ice cream as a frozen pie for a royal banquet.

Legend has it that Mirco's ice cream pie was so well received that King Charles commanded the chef to keep its recipe a secret, and he paid him a yearly retainer of £500 to ensure his silence.

However, after Charles I was beheaded in January 1649, the artful chef sold the frozen pie recipe to wealthy noblemen and the secret was out.

It is recorded that Charles II (1630–1685), the son and successor of Charles I, enjoyed eating ice cream throughout his 9-year exile in France. When he was proclaimed King of England in May 1660, ice cream had become so popular among the English nobility that some of the wealthiest noblemen actually had straw-thatched ice-houses dug into the ground to enable ice to be kept the year-round.

The treasured ice was harvested by servants in the winter from frozen lakes and rivers and was used to freeze ice creams and water ices and to chill beverages.

Ice cream came to symbolize the highest position of rank and privilege, and the noblemen were very careful to preserve the secret of its preparation so servants involved in ice cream making were sworn to secrecy.

Few people of lesser rank had ever tasted ice cream, and many peasants had never even heard of it.

History records that Charles II had ice cream and white strawberries served at a banquet for the Feast of St. George at Windsor Castle in 1671, but only those seated at the king's table got to taste the delicacy while the guests of lower rank looked on with envy.

But, as with any enticing secret, it was only a matter of time before the method of ice cream making would be shown to all.

The first English cookbook to reveal ice cream making and feature an ice cream recipe was "Mrs. Mary Eales Receipts" published in 1718.

Mary Eales had been the royal confectioner to King William III of Orange (1650–1702) and later to Queen Anne (1665–1714), the daughter of James II (1633–1701).

Mrs. Eales perfected the art of ice cream making during her stint at the royal palace, and she made the decision to publish her knowledge of confectionery and ice cream making upon her retirement from the royal household after the death of Queen Anne.

At last, ice cream making was now possible for those outside the nobility who were literate and could afford the price of the cookbook.

Meanwhile, the chefs in France had also tried to keep the secret of ice cream making exclusively for the nobility, but they too were unsuccessful as the desire for pecuniary gain eventually won out.

The first public ice cream parlor in Paris was opened in 1670 by a Sicilian named Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli. He called his new parlor Café Procope believing the name "Procope" would be more inviting to the French ear than Procopio.

Coltelli's new business proved so successful that he soon had to move to a larger location in the Quartier Latin.

Luminaries like Rousseau, Voltaire, Balzac, Victor Hugo and Napoleon frequented Le Procope and after three centuries the cafe still serves its marvelous ice cream and is the oldest and best-known cafe in Paris.

Voltaire (Arm Raised) at Le Procope

Voltaire (Arm Raised) at Le Procope(PD Source: Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Coltelli used an ice cream freezer invented by his grandfather, Francesco, a humble fisherman, to manufacture frozen ices flavored with vanilla, strawberry, and chocolate; however, soon he developed other Parisian favorites such as macaroon and rum and raisin.

Coltelli's exotic ices were unequaled to that time and King Louis XIV (1638–1715) recognized his genius by granting him exclusive rights for the commercial production of ice cream.

The Georgian Era In Ice Cream History

In Monsieur Emy's archaic style of French writing, it was the practice to use a "long-s" character having the "appearance" of the letter f with a half-crossbar on the left-hand side.

Simply substitute an "s" for the ſ and the word makes sense.

When Monsieur Emy of Paris published his classic "L'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces D'Office" in 1768, ice creams and water ices had become widely popular throughout England and in all the major European cities.

Emy's book on the art of artificially freezing ices provides readers with not only a thorough scientific explanation for the artificial freezing of liquid mixtures using salt and nitrates mixed with ice, but it also gives detailed recipes for freezing a wide variety of frozen ice cream desserts.

Concerning the originator of artificial freezing techniques, Emy writes that "c'eſt Alexandre le Grand, qui en a donné les premieres idées," justifying his claim that Alexander the Great was the first to recognize the possibility of preserving ice the year-round

Emy explained how Alexander's soldiers accidentally discovered deposits of ice underground in warm climates when they dug deep wells or pits during his many conquests.

Il n'eſt pas fait mention dans l'Hiſtoire que ce qrand Prince ſe ſoit occupé à cette partie de la Phyſique: il faut donc croire que c'eſt le haſard qui aura donné lieu à cette découverte; que peut-être dans le cours de ſes conquêtes, ſes Soldats, en creuſant la terre pour faire des puits, ou tous autres trous pour leur utilité, auront trouvé de la glace ſouterreine, comme on en trouve encore pendant les chaleurs de l'Eté à la Chine, dans la Tartarie Chinoiſe, dans l'Arménie, dans la Glaciere de la Franche-Comte à cinq lieues de Beſançon, & dans tous les endroits abondans en ſel ammoniac. —Emy. "L'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces D'Office"1

Emy suggests in the above quoted passage that Alexander, surprised by the phenomenon of finding ice beneath the earth's surface in the summer, ordered essays to be written to see whether it would be possible to preserve ice the year-round.

He credits Alexander's initiative for making possible the enjoyment of the frozen refreshments that everyone now loves and takes for granted.

Ils furent ſans doute très-étonnés de ce phénomene; Alexandre aura ordonné de faire des eſſais, pour voir s'il étoit poſſible d'en conſerver toute l'année; … C'est par le ſecours de cette invention que nous jouiſſons des rafraîchſſemens, qui font les délices de nos meilleures tables, & qu'en Eté on prend avec tant de plaiſir. —Emy. "L'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces D'Office"2

Emy also proposes that England's Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was the first to mention the properties of salt to lower the temperature of ice water.

He quotes from a scientific paper of Bacon's saying, "it is evident that the salt which one mixes with ice for artificial freezing increases the action of the cold":

"Le Chancelier Bacon eſt le premier qui ait fait mention des proprietés du ſel & nitre: il dit qu'il eſt évident que le ſel que l'on méle à la Glace pour les congelations artificielles augmente l'action du froid."3

Emy concludes that Bacon's observations provide "certain proof that salt and nitrates were being used in his time" during the Stuart Era in the early part of the sixteenth century.

The French chefs in Emy's day excelled at molding ices into colorful, artistic creations such as miniature castles, exquisite floral arrangements, unicorns, horses, and all manners of wildlife.

At one grand dinner given by Louis XIV, Monsieur L. Audiger, the royal confectioner famous throughout Europe for his molded ice creams, served decorated Easter eggs sitting in costly silver cups. Surprised guests soon discovered that what appeared to be exquisitely hand-colored eggs were actually molded ices.

The famous chef Vatel was also known to have prepared a frozen dessert shaped like eggs for one of Louis XIV's banquets and in 1774, the Duc de Chartres gave a lavish banquet that ended with a spectacular dessert featuring his colorful coat of arms hand-carved in glistening ice cream.

These early ice cream desserts were laboriously frozen in a covered freezing pot called a sarbotiere. These pots were often made of pewter, and they were immersed in a finely crafted wooden bucket filled with chipped ice and either saltpetre or coarse rock salt.

The ice cream mixture had to be beaten by hand and poured into the sarbotiere, which then had to be agitated to freeze the cream.

The method used was to hold the sarbotiere by its handle and rapidly swish it up and down in the bucket of ice water while simultaneously rotating it right and left in a strenuous wrist action that had to be maintained for up to an hour!

Occasionally, the semi-frozen mixture was scraped from the sides of the sarbotiere with a "houlette" or what the English called a "spaddle," a small spade-like spatula with a long handle, and again beaten.

Houlette, Sarbotiere, and Cherubs Making Ice Cream

Houlette, Sarbotiere, and Cherubs Making Ice Cream(PD Source: L'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces D'Office, Emy, 1768)

The eighteenth century woodcut (above) shows a houlette or spaddle and a typical sarbotiere of that era with its lid and handle.

To make ice cream, you had to remove the lid and place the ice cream mixture inside the sarbotiere. You would then re-seal the sarbotiere and place it inside its "seau" or wooden ice bucket as shown, and the bucket was then filled with a mixture of ice and salt.

The cherubs depicted in the remarkable woodcut are involved with the entire process of ice cream making. They can be seen busily bringing fresh fruit from the garden, crushing it and preparing it for freezing, agitating the sarbotieres in their buckets to freeze the ice cream mixture, scraping the semi-frozen mixture from the sides of the sarbotiere using a houlette, and spooning the finished ice cream into ornate ice cream goblets for serving.

Because of the excessive time and labor involved in making ice cream, and the requirement for a year-round source of ice, for many years ice cream remained a special treat reserved for well-off families with servants.

The first sarbotieres were either specially ordered from an artisan or homemade, but by the early 1700s they were being manufactured and sold commercially as frozen desserts quickly gained popularity among the well off in England, France, Italy, and elsewhere.

Antique Sarbotieres of Italian Origin

Antique Sarbotieres of Italian Origin(Source: ©Alan, used with permission)

The French and British settlers probably brought knowledge of ice cream making to North America around this time, and some of the governing class may even have brought their own sarbotieres.

France's fortified colony of Louisburg on Ile Royale (Canada's Cape Breton Island) enjoyed a proper French cuisine and before the fort's destruction in 1758, its commanders likely enjoyed ice cream.

It is certain that the new immigrants brought cookbooks with them including, perhaps, M. Emy's.

One of the most famous English cookery writers of the eighteenth century was Elizabeth Raffald (1733–1781). Pioneer women hungering for the elegant meals they once enjoyed back in the Old Country particularly treasured her detailed recipes.

In 1769 Raffald wrote, "The Experienced Engliſh Houſe-keeper," which was to become her best-known cookbook, and its popularity no doubt crossed the Atlantic. Her book contains a practical recipe for making a tasty apricot ice cream:

Apricot Ice Cream Recipe

Pare, stone and scald twelve ripe Apricots, beat them fine in a Marble Mortar, put to them six Ounces of double refined Sugar, a Pint of scalding Cream, work it through a Hair Sieve, put it into a Tin that has a close Cover, set it in a Tub of Ice broken small, and a large Quantity of Salt put amongst it, when you see your Cream grow thick round the Edges of your Tin, stir it and set it in again 'till it all grows quite thick, when your Cream is all Froze up, take it out of your Tin, and put it in the Mould you intend it to be turned out of, then put on the Lid, and have ready another Tub with Ice and Salt in as before, put your Mould in the Middle, and lay your Ice under and over it, let it stand four or five Hours, dip your Tin in warm Water when you turn it out; if it be Summer, you must not turn it out 'till the Moment you want tt; you may use any Sort of Fruit if you have not Apricots, only observe to work it fine. —Elizabeth Rafald, 1769.4

Ice cream soon became a very popular delicacy in the New World and in 1774, a newly arrived British confectioner named Philip Lenzi took out a large display ad in a New York newspaper to announce that he could supply a quality line of confections "including ice cream" on special order to the local carriage trade.

It was also in 1774 that ice cream was served at a formal dinner in Annapolis hosted by Governor Thomas Bladen (1698–1780) of Maryland.

A Virginian commissioner named William Black, an appreciative guest at Governor Bladen's dinner, later published his journal wherein he describes "a Dessert no less Curious; Among the Rarities of which it was Compos'd, was some fine Ice Cream which, with the Strawberries and Milk, eat Most Deliciously."

Public demand for ice cream continued to grow, and the first commercial ice cream parlor in America opened in New York City in 1776. It was around this time that egg yolks were first used in France to make richer-tasting, custard-based ice creams that were thereafter called French-style ice creams.

People loved the newer and richer ice cream taste, and the new frozen custard recipes quickly spread beyond the borders of France to England and to North America.

Much of the ice cream making in Colonial America had been centered in Philadelphia and ice cream made without eggs became known in America as Philadelphia-style ice cream to differentiate it from the newer French-style ice cream.

It is not recorded when General George Washington (1732–1799) tasted his first ice cream, but we do know that he ate it in Philadelphia in 1785 at a lavish party given by the French minister, Monsieur de la Luzeme, to celebrate the birth of the Dauphin of France.5

Washington often requested ice cream to be served at formal White House dinners throughout his 1789–97 presidency, and he was often a guest at the elegant parties thrown by Mrs. Elizabeth (Betsy) Hamilton, the wife of Alexander Hamilton, the nation's first secretary of the treasury during Washington's administration, where "pyramids of red and white ice cream with rose and cinnamon" were the center of attraction.

During the warm summer of 1790, according to the records of a confectionery merchant on Chetham Street, New York City, Washington spent about $200 for ice cream; an extravagant figure for his time—a small fortune in today's currency.

An inventory took after Washington's death lists "two pewter pots" used for the storing of ice cream. Washington likely used these pots to serve his guests generous helpings of ice cream along with cake and chilled lemonade at the English-style levees he held at Mount Vernon.

Two of Washington's contemporaries, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) and Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), also loved to eat frozen desserts.

Franklin became well acquainted with ice cream during his stay in Paris where he was a frequent visitor to Le Procope.

Jefferson also enjoyed Le Procope's ice creams during his stint as ambassador to Paris, and he employed an experienced French chef who taught him the secrets of ice cream making.

Before he had returned to America from Paris in 1789, Jefferson hand copied out his favorite recipes for French-style ice cream. One of Jefferson's recipes is now a noteworthy part of ice cream history for being America's oldest-known handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream.

Jefferson obtained his own sarbotiere, and it wasn't long before he had an ice-house built at Monticello so that he could indulge in making ice cream the year-round.

He loved to eat French-style vanilla ice cream, and on at least one occasion he had a special order of vanilla bean pods sent to him from Paris. Jefferson's distinctive vanilla ice cream was often served to favored guests at Monticello.

During Jefferson's 1801–09 presidency, one White House dinner guest wrote that he enjoyed an unusual ice cream served "in the form of small balls, enclosed in cases of warm pastry" and that it was "very good, crust wholly dried, crumbled into thin flakes"; it was very similar to what is now called deep-fried ice cream on some menus.

Dolley Payne Madison, the wife of President James Madison (1751–1836) and the U.S.'s "first" First Lady, became famous for her lavish balls and parties. She often served elaborately molded ice creams at White House receptions while acting as hostess for the widowed Thomas Jefferson and later as hostess during her husband's presidency.

Dolley is credited for making ice cream a fashionable dessert after she ventured to serve a shimmering "tower" of pink, strawberry ice cream on a large silver platter at Madison's second Inaugural Ball in 1812.

It was prepared by Chef Augustus Jackson using fresh cream from the Madison's dairy at Montpelier and freshly picked strawberries from Dolley's own White House garden. Soon, fancy ice creams and molded ices were being served at fashionable events in all the major cities.

The Victorian Era In Ice Cream History

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, though ice creams and water ices were universally talked about, they were not universally enjoyed.

Few of the general population had ever tasted ice cream for it was still considered a luxury and difficult to make. Ice and salt had to be packed in a wooden tub. So, unless there had been a ready supply of river ice stored in an ice-house, ice cream making had to be relegated to the winter months.

And making it was a grueling, time-consuming task that the wealthy simply handed over to their servants or slaves and the middle-class avoided by their ability to purchase the expensive confection.

Most common folk, however, simply did without ice cream or they made it in the winter months only on very special occasions.

Tired of the time and effort involved in making ices, Nancy Johnson, an enterprising New England housewife, invented America's first mechanical ice cream freezer.

Powered by a hand crank, her brainchild featured an S-shaped dasher that efficiently scraped the sides of the pot as it revolved to prevent ice crystals from forming.

Compared to the old sarbotiere-style pot freezers, Johnson's freezer froze the mixture faster and with much less effort. It was a clever idea, and its basic design is still in use today.

Johnson was awarded a U.S. patent for her Artificial Freezer invention on September 9, 1843 (Letters Patent No. 3254). Later, lacking money for mass production, she sold all rights to her invention for $200 to William G. Young, a wholesaler.

On May 30, 1848, William G. Young of Baltimore patented Johnson's freezer "with new and useful improvements" (Letters Patent No. 5601). He must have been a decent fellow for he generously acknowledged Nancy by naming his new acquisition the "Johnson Patent Ice-Cream Freezer."

Young manufactured and marketed the Johnson-style freezers at the affordable price of $3 each, and the mechanical ice cream freezer quickly captured the public's attention bringing ice cream making to a much wider segment of the population.

The new freezers were not only used in homes, but they were also used in small confectionery shops and restaurants to make ice cream faster and more affordable; then as now, time meant money.

Soon, many companies became involved in manufacturing hand-cranked ice cream freezers patterned after Nancy Johnson's and numerous patents were issued as entrepreneurs endeavored to improve the basic design.

Some of these companies continued to manufacture ice cream freezers until after the turn of the century.

For instance, one of the best known, The White Mountain Freezer Company, began making ice cream churns in 1872. They soon became renowned for the exceptional workmanship of their freezers and the company continues to manufacture their original, hand-cranked, wooden ice cream freezer today under new ownership.

Ice Cream Churns in the 1890s

Ice Cream Churns in the 1890s(PD Source: Dainty Dishes, 1900)

As more ice cream freezers were purchased, more ice was needed, and this prompted the widespread growth of insulated ice-houses. By the 1850s, companies were shipping ice blocks by stern-wheeler riverboats from the northern states to ice dealers in the warmer south.

Plantation owners had slaves build underground ice-houses so that they could store ice to freeze their ice cream and chill their mint juleps throughout the warm Southern summers.

In 1851 Dr. John Gorrie invented the first commercial machine for making ice. His invention would eventually supply the huge quantities of ice needed for ice cream production and storage, and by the end of the 19th century there were over 400 ice plants operating in the United States.

It was only a short time before the mechanical ice cream freezer found its way to Victorian England, and there too, it revolutionized the making of ice cream. Soon, the treat that was once the delicacy of kings and queens became within the reach of most British subjects.

Rock salt became inexpensive and readily available, and so much of it became used in ice cream making that people began to call it ice cream salt.

Shiploads of ice were imported from Canada, the United States, and Norway, and taken by canal barges to inland ice-houses to meet the manufacturing demands of the frozen confectionery industry.

British chemists even developed special freezing powders to freeze ice cream mixtures through a chemical process when natural ice was scarce domestically or unobtainable in the far off tropical regions of the Empire.

The next major development in the growth of the ice cream industry came in 1851 when a Baltimore milk dealer by the name of Jacob Fussell founded America's first commercial ice cream plant as a means to ensure a steady demand for his cream. Up to this time, ice cream had always been made on the premises of the seller.

Fussell astutely sold his product for less than half the price of his competitors and his business became so successful that he abandoned his milk business and went into full-time ice cream production.

Between 1851 and 1864 Fussell opened other wholesale ice cream plants in Washington, Boston, and New York. Now, affordable, factory-made ice cream was readily available to most Americans, including those living in small towns and villages.

As the country's population expanded westward, a protégé of Jacob Fussell, Perry Brazelton, opened a wholesale ice cream plant in St. Louis in 1858. Soon after, he built a second plant in Chicago and another in Cincinnati soon after that.

A traveling British author invited to a Longworths family get-together in Cincinnati during the unusually warm autumn of 1858, describes the generous "piles of Vanilla ice"—ice cream—served for evening refreshments:

"Towards ten o'clock a table was laid out in the drawing room with their Catawaba Champagne, which was handed round in tumblers, followed by piles of Vanilla ice a foot and a half high. There were two of these towers of Babel on the table, and each person was given a supply that would have served for half a dozen in England; the cream however is so light in this country that a great deal more can be taken of it than in England; ices are extremely good and cheap all over America; even in very small towns they are to be had as good as in the large ones. Water ices or fruit ices are rare; they are almost always of Vanilla cream. In summer, a stewed peach is sometimes added."6

The 1860s found ice cream parlors and ice cream saloons scattered throughout every large city and in almost every town and village. Parlors and saloons looked very much alike; both were decorated with ornate metal tables and gilt-framed mirrors, but the parlors were often a little bit fancier with carpeted floors.

Many of these old-fashioned ice cream shops featured sloping glass cases filled with penny candies and fine chocolates, and some even had a soda fountain; however, this was before anyone had discovered the taste benefit of adding ice cream to sodas.

The pharmacy soda fountain was another place where one could often buy ice cream then, and many fine restaurants included ice cream on their menus.

After the soldiers had returned home from the American Civil War in 1865, it became difficult to find work, and many unemployed immigrants became ice cream vendors in the major cities.

As in London, England, they were called Hokey-Pokey men because they often shouted Ecco un poco in Italian which loosely translated means, "Here's a little piece."

The term hokey-pokey soon became identified with poor-quality ice cream, as it was sometimes made of questionable ingredients under very unsanitary conditions, and it was not uncommon for consumers to become ill after eating it.

Hokey pokey ice cream was sold from pushcarts, and the customers either licked it out of a shallow glass known as a "penny lick" or it was received hand-wrapped in waxed paper. When they had finished eating the ice cream, the glass was returned to the vendor who simply gave it a brisk wipe with his cloth before filling it for the next customer.

Necessity being the mother of invention, an unsuspecting soda vendor did much to increase the sales of ice cream thereby proving that old maxim. At the Philadelphia Exposition in 1874, Robert M. Green is credited with inventing the popular "ice cream soda" when he conjoined two of the world's most popular treats—soda pop and ice cream.

Green usually made a soft drink called a cream soda from sweet cream, fountain syrup, and carbonated water, but he ran out of sweet cream and added a scoop of homemade vanilla ice cream to his customers' sodas instead. The cold, refreshing beverage that he created proved to be so popular that it's said his profits rose from $6 to $600 in a single day!

News of Green's ice cream sodas spread quickly and soon trendy ice cream parlors and pharmacy soda fountains everywhere began offering the new taste sensation forcing the ice cream manufacturers to increase their production to meet the new demands.

In 1878 William Clewell of Pennsylvania patented the first ice cream scoop to enable fountain operators to add a measured amount of ice cream to soda glasses more efficiently.

And untold numbers of both soda jerks and ice cream lovers have since used metal scoops based on Clewell's classic, non-mechanical design to pry rock-hard ice cream from its container.

As increasing numbers of pharmacy soda fountains had begun to serve ice cream, the ice cream parlors faced increasingly stiffer competition and the differences between the menus of the two operations began to blur.

The small marble soda fountains had been popular with fountain operators until about 1880. Now the new "wall" or "back-bar" soda fountains began to appear in answer to the problem of where to put all the bulky containers of ice cream.

Beginning as medium-sized utility cabinets, they quickly grew larger and more ornate to satisfy the demand for new soda flavors and more ice creams and confections.

Exotic looking and crafted of fine marbles and onyx, wall fountains were richly embellished with silver-plated mirrors, gas lighting fixtures, and detailed woodcarvings.

They combined an efficient work area with a convenient storage facility and consisted of an ornate bar set against the wall behind the marble serving counter.

The bar was an imposing structure about four or more feet high with a polished wood or marble cornice supported on the two sides by columns of similar material and containing shelves for displays of confections, herbal teas, and cigars, with a large mirror in the center.

Syrup spigots were arranged along the back of the countertop and located beneath the counter were the soda fountain apparatus and the bulky ice chests for the ice cream tubs and cooling. The appearance of these wall fountains somewhat resembled the old saloon bars seen in western movies.

It was in 1881 while visiting an ice cream parlor in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, that a teenager named George Hallauer is credited with inventing the ice cream sundae.

It's alleged that Hallauer spontaneously asked the fountain operator, Ed Berner, to drizzle chocolate syrup over his dish of plain ice cream. However, there are other credible sources that indicate the sundae wasn't invented until some time in the 1890s.

Drinking soda water was considered improper by some Victorians and various Midwest towns even passed laws preventing its sale on Sundays; the so-called "soda suckers" were even vilified in sermons and in the popular press then.

A clever pharmacist in Evanston, Indiana created an alternative taste treat to sell on Sundays that contained soda fountain syrups and ice cream but no soda water.

Meanwhile, over in Wisconsin, George Giffy and other soda fountain owners also began to sell what were cleverly called "legal ice cream sodas"—that is, sodas without the soda—on Sundays, offering the customer a choice of ice cream and flavouring syrups for only 5 cents.

The new ice cream and fountain syrup combination became quite popular, and people began calling it a "Sunday soda" or simply a "Sunday." They were only sold on Sundays at the beginning, but soon people began to ask for them on other days of the week too.

Eventually, the spelling was changed from Sunday to "sundae" out of respect for the Lord's Day and to make the treat popular during the rest of the week.

It was around this time also that the ice cream sandwich and the ice cream float appeared, but no one really knows the exact date or who it was that invented them.

Many popular treats were developed spontaneously as customers demanded combinations of their favourite ingredients.

Ice Cream History From the Edwardian Era to World War Two

Sanitary Ice Cream Cone Co., Oklahoma City - 1917

Sanitary Ice Cream Cone Co., Oklahoma City - 1917(PD Source: Library of Congress LC-USZ62-83928)

Factories making ice cream and ice cream cones remained surprisingly small up until the turn of the century and sometimes employed schoolchildren working long hours into the evenings.

The invention of the centrifugal cream separator in 1867 helped to speed up production of the cream, but even up until the end of the 1890s, ice cream factories consisted mostly of a roomful of workers busy cranking ice cream freezers—it presents a rather quaint image.

But, starting with the invention of the homogenizer by Gaulin of France in 1899, new advances in technology in the early 1900s soon effected great changes. The introduction of steam-powered automation, mechanical refrigeration, and the gasoline engine caused the ice cream industry to grow dramatically.

Before these innovations, ice cream had to be consumed within hours of being manufactured, and it couldn't be shipped long distances. Now, thanks to refrigeration and motorized delivery trucks, it was possible to store and ship ice cream and other perishable foods in large quantities.

Ice cream now became a mass-market product, and so its retail prices dropped. The unfortunate offshoot was that people began to make less ice cream at home.

They were ever more drawn to the affordable, store-bought ice cream sold by dairies and confectioners who were becoming increasingly clever at coming up with new ways to promote it.

Another innovation that caught the attention of customers was the invention of the "front-service" soda fountain by Dr. Heisinger in 1903; its debut signaled the demise of the smaller, less-efficient fountains.

The efficient front-service fountains incorporated all the necessary features for the preparation and serving of ice cream sodas and sundaes in one logical, functional unit that stood between the operator and the customers.

An assortment of soda fountain syrups was drawn from an impressive bank of automatic, silver-plated faucets built into the marble countertop. These new-style faucets standardized flavours and eliminated waste by accurately dispensing measured amounts of fountain syrup.

Prominently centered on the countertop, a pair of tall, shiny draft taps on an onyx base dispensed the chilled soda water, while nearest the operator an impressive row of deep, insulated wells located in front of the faucets held a wide assortment of ice cream flavors.

Everything was made within easy reach of the operator, and the customer could clearly view the fascinating dispensing operation.

The parlor itself was richly decorated with silver-plated lighting fixtures crowned with colorful Tiffany shades, and the wall behind the counter often featured massive plate-glass mirrors with carved marble and onyx frames, giving the impression of opulence and spaciousness.

Because floor space had been at a premium, a row of revolving stools in front of the serving counter and sets of dainty chairs and glass-topped tables artistically constructed of white-painted metal provided practical seating fof customers.

The rich appearance of the gleaming front-service fountain and its modern automation served to attract customers in the face of growing competition from the soda bottlers and itinerant ice cream vendors.

Zaharako's Ice Cream Parlor, Columbus, IN

Zaharako's Ice Cream Parlor, Columbus, IN(Source: Library of Congress HABS IND,3-Colu,1--2)

There was also much innovation in the manner in which ice cream was packaged. Profitable new ways were found to sell ice cream in individual servings to impulse buyers.

A pushcart ice cream vendor on New York's Wall Street named Italo Marchiony looked for an easier and more practical way to sell his lemon ice cream to customers without the bother of having to use the glass penny lickers.

Not only did the glasses have to be returned and wiped clean, but also customers sometimes dropped them or simply walked off with them. And some customers rightly refused them for sanitary reasons. This all added to the cost of doing business.

In a stroke of genius Marchiony baked a crisp, cup-like pastry with sloping sides and a flat bottom to use as a walk-away container. The edible cup was a tremendous hit with his customers, and he filed a U.S. patent for it in September 1903 claiming that he had made the edible cups since 1896. Industry has since voted the edible pastry cup an example of an environmentally perfect container.

Marchiony might have invented a flat-bottomed edible cup, but he did not invent the first edible ice cream cone or "cornet" as the British people prefer to call them; evidence of an earlier edible container has surfaced.

In 1888 Agnus Bertha Marshall (1855–1905) published Mrs. A. B. Marshall's Book of Cookery in London, England, which made a clear reference to custard cones in her recipe "Cornets with Cream."

All told Marshall wrote four popular cookbooks, including two on the subject of ice cream making: The Book of Ices in 1885 and Fancy Ices in 1894. Both books contain a recipe for cornets or "comet casings" made of flour, sugar, eggs, vanilla, ground almonds, and rose water.

Marshall's cookbooks also featured recipes for exotic ices such as Parisian Cucumber Cream, Brown Bread Soufflé, Gooseberry Sorbet, Monte Carlo Violet Ice, and Battenberg Ice.

It always surprises people to learn that despite the many flavors manufactured by today's ice cream manufacturers, there are really very few new flavors under the sun!

Mrs. Marshall lectured extensively on cookery and became quite well known throughout the United Kingdom. She eventually founded her own successful cooking school called the Mortimer Street School of Cookery.

And, Marshall also patented and sold her own cooking equipment and a variety of decorative ice cream molds which are now valuable collectibles.

Marshall also patented an ice cream freezer with a unique design. It was wider and shallower than the American Johnson-type and was thought to produce a much creamier ice cream.

Her popular cookbooks with their exotic ice cream recipes served to create a huge demand for elegant ice cream desserts during the late-Victorian Era.

A Syrian pastry vendor from Damascus named Ernest A. Hamwi is credited with creating the first waffle-type ice cream cone at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.

Hamwi ingeniously rolled a thin, crispy, waffle-like Persian pastry called zalabia into a handy cone-shaped holder for a scoop of ice cream after a nearby ice cream vendor—some say it was Charles E. Menches—ran out of glass penny lickers.

After the fair, Hamwi and his financial backers successfully opened the Cornucopia Waffle Company and later the Missouri Cone Company; however, he was not the only one to claim the invention.

Charles E. Menches, Abe Doumar, David Avayou, Arnold Fornachow, and Albert and Nick Kabbaz, all claimed ownership and they were all vendors at same World's Fair.

Despite who invented it first, the popularity of the "World's Fair Cornucopia" spread quickly worldwide and the rolled, crispy waffle cone is still popular today.

Also in 1904, David Strickler, a young soda fountain operator in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, is said to have invented the world's first "banana split" when he placed three scoops of vanilla ice cream on a split banana and garnished it with chocolate syrup, marshmallow, nuts, whipped cream, and a big red maraschino cherry. It cost only ten cents!

Soon, other soda fountain operators began making banana splits and the classic sundae evolved into a scoop each of chocolate, strawberry, and vanilla ice cream on a split banana with a garnish of three different syrups, chopped nuts, whipped cream, and the essential red maraschino cherry. Today, the banana split still rules as the king of sundaes.

An eleven-year-old boy named Frank Epperson accidentally invented the Popsicle® in 1905. He mixed himself a citrus-flavoured effervescent soda one evening, and he left it sitting on the back porch while he ran off to play ball. He forgot all about drinking it, and it sat outside overnight in freezing temperatures.

The next morning, when Epperson discovered his glass still sitting on the porch, his drink was frozen solid with the spoon still in it. Grasping the spoon, he pulled the frozen soda from the glass and found that it tasted delicious, and so he proceeded to make similar frozen sodas for his friends.

But, it wasn't until around 1922 that an older Epperson suddenly realized itsrue potential and filed a patent for his "frozen ice on a stick." He began selling "Epsicles" in "7 fruity flavours," but he later changed the name to Popsicle®, and by 1928 he had earned royalties on more than 60 million sold!

Harry Burt invented the familiar Good Humor® ice cream bar in 1920. The following year, in 1921, Chris Nelson wrapped a small, thick square of frozen vanilla ice cream in waxed paper and he cleverly named it the "I-Scream-Bar."

Later, after a successful year of sales, he dipped the square of ice cream into melted chocolate to make the first Eskimo Pie®

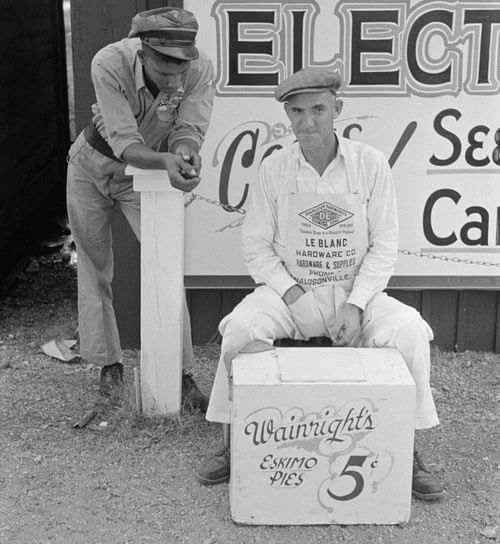

Eskimo Pie Vendor in Donaldsonville, LA - 1938

Eskimo Pie Vendor in Donaldsonville, LA - 1938(PD Source: Library of Congress LC-USF33-011786-M4)

About the same time, Chester Isaly dipped a bar of ice cream into melted Swiss chocolate and created the Klondike Bar®, which he named after the site of Canada's greatest Gold Rush in 1896–99.

These tasty ice cream treats opened the door to the veritable flood of popular frozen confections that we find at stores today.

Yet, even with all the tasty commercial products available, nothing beats the taste of good, old-fashioned, homemade ice cream!

Ice cream and soda parlors continued to attract ice cream lovers throughout the first half of the twentieth century and, except for refinements resulting from innovations in technology and product evolution, the front-service fountains remained in much the same form until their demise in the 1960s.

The introduction of the cream homogenizer, steam power, electric motors, and packing machines did bring changes to the ice cream industry, but the developments of mechanical refrigeration and motor vehicle transport effected the biggest change in ice cream history.

Modern refrigeration eliminated the need for the bulky ice chests, and it stopped the steady flow of expenses involved in delivering and packing the ice needed to store the ice cream.

Motorized delivery trucks quickly and efficiently delivered ice cream and other frozen dessert products to the shops and permitted the shop owners to take ice cream directly to the customer.

For example, in the photo below a vintage ice cream truck poses outside Bury's Drug Store and ice cream parlor, proudly decorated and ready to depart for a city park or baseball game on a 4th of July weekend about 1919.

Ice Cream Truck Parked Outside an Ice Cream Parlor on July 4, 1919

Ice Cream Truck Parked Outside an Ice Cream Parlor on July 4, 1919(Source: Library of Congress LC-USZ62-67433)

As the cost of transport and refrigeration units dropped, more neighborhood parlors opened for business.

By the 1930s, ice cream was everybody's favorite treat. Even President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945) confessed in 1935 that he liked to eat ice cream at least once a day.

It was common back then to find ice cream parlors located nearby movie theaters and high schools. They were an integral part of the social scene and a friendly place for friends and family to "hang out" after school or church to enjoy a milk shake or a sundae beneath the soft breeze of the whirring ceiling fans.

It's said that movie star Ingrid Bergman (1915–1982) absolutely loved ice cream parlors and hot fudge sundaes so much when she first arrived in New York in 1939, the Hollywood casting directors became concerned she would gain too much weight for her movie roles.

Many older students earned their pocket money, and some even put themselves through college by working as white-jacketed "soda jerks," which was the job title given to those who deftly dispensed ice cream sodas and milk shakes with a proud flourish.

In 1938, the year before the start of World War II (Canada entered the war in 1939 whereas the U.S. did not enter the war until December 1941), J. F. McCullough and his son Alex invented a new soft-serve ice cream.

Grandpa McCullough had been seeking a way to serve a soft, creamy ice cream believing that semi-frozen or softened ice cream was more flavorful.

They developed a successful ice cream mix and after a difficult search they found a freezing machine that they could modify to dispense the soft ice cream.

Eventually, the first Dairy Queen® store opened in Joliet, Illinois in 1940 selling the new soft ice cream for 5 cents a cone or 8 cents for a sundae.

Grandpa McCullough named his product Dairy Queen® because he believed it was the "queen" of dairy products. He was one of the first to embrace franchising, and he saw his postwar soft ice cream business grow beyond his wildest dreams.

Ice Cream History From World War Two to the Present Day

The Aircraft Carrier USS Lexington

The Aircraft Carrier USS Lexington(PD Source: Library of Congress LC-DIG-highsm-29503)

On May 8, 1942 the aircraft carrier USS Lexington was torpedoed during World War II's famous Battle of the Coral Sea.

When it had become apparent that the Lady Lex would soon sink, some members of the crew used their helmets as bowls and brought ice cream up from the ship's store to eat on the flight deck while waiting for the abandon ship order.

Thinking back to that day, Wood Richmond, one of the sailors who "rescued" the ice cream admitted, "The ice cream tasted pretty good."7

The American military recognized the benefits of serving ice cream for maintaining troop moral during World War II, and the U.S. Navy outfitted its aircraft carriers with ice cream makers. They often rewarded escort destroyers with 20 gallons of ice cream every time they rescued a downed pilot from the sea.

Ice cream was so popular with the American troops that the U.S. Navy commissioned the world's first floating ice cream parlor in 1945—a floating concrete barge with facilities to manufacture and dispense ice cream to the Pacific fleet.

Ice cream freezers were not standard issue for World War II submarines because of their space restrictions, but that didn't stop some crafty sailors aboard the USS Pampanito; they simply "appropriated" a 3-gallon Lang-Sherman Co. freezer for the use of the crew.8

The freezing-cold ice cream was a welcome relief for the sailors living in the hot, cramped quarters of a sub. The only other sub to have the luxury of an ice cream freezer was the USS Tang.

North America's Ice cream and soda parlors couldn't always get a steady supply of ice cream during wartime because of the necessary rationing of sugar and dairy products. To compensate, they added other menu items like sandwiches and pastries.

Even before the war the pharmacy soda fountains were busily installing toasters and grills and began to offer doughnuts, hot dogs, hamburgers, soups, and hot sandwiches as standard fare at their new "lunch counters."

The added food items brought in business the year-round, and the lunch counters became a familiar hangout for shoppers and the after-school, teen crowd.

World War II restricted ice cream making in the home as well. The strict rationing of sugar meant it could not be used frivolously for the making of treats. The average family's sugar ration coupons were used only for the basic needs so people discovered other snacks and forms of entertainment.

After the war ended in 1945, products no longer had to be rationed. Sugar and dairy products now became plentiful, and people again indulged in making ice cream.

But, the times had changed; there seemed to be less inclination to make one's own ice cream. Dozens of readily available commercial ice cream products flooded the market during the time of booming postwar prosperity.

In the early 1950s nothing changed people's lifestyles as much as television. This new medium quickly became the source of entertainment in the home, and watching it required one's full attention leaving no time for ice cream making.

Bolstering Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan's observation that "the medium is the message," television's effect was so phenomenal that people were lured to watch even the commercials — commercials that relentlessly promoted commercial ice cream products such as ice cream bars, Dairy Queen® Cones, and Popsicle® treats.

Soon, few families gathered around the ice cream freezer. Most preferred to bring their treats home from the corner store or supermarket.

Postwar Wicks Family Making Ice Cream - 1946

Postwar Wicks Family Making Ice Cream - 1946(Source: Library of Congress, LC-G612-T-48402)

Though the ice cream parlors did a brisk business soon after the war ended, they too were on the verge of experiencing great change. The 1950s would see the parlors enter a state of steady decline so that by the end of the 1960s, few would survive.

Several reasons effected this shift; the major reason being the dramatic change in the public's buying habits. As cars had become more plentiful, and as people became accustomed to traveling and eating out, small luncheonettes and diners sprang up to draw customers from the parlors and soda fountains.

These forerunners of the fast-food restaurants also offered ice cream sodas, milk shakes, and sundaes, along with an expanded menu of quick and tasty, low-priced meals and roomier more comfortable seating. It was extremely hard to compete.

Also, the introduction of take-home pint bricks and half-gallon cartons of ice cream and the phenomenal growth of supermarkets led to more pre-packaged ice cream products being sold.

Gradually, more people were influenced to enjoy their ice cream and soda pop at home, and the traditional ice cream parlors and soda fountains soon lost ground.

Soon, ice cream recipes and ice cream freezers almost disappeared from the nation's kitchens and many young people grew up never learning to make homemade ice cream or knowing what it was like to lick a frozen dasher.

By the 1960s, life seemed to have become faster and busier and terms like "instant" and "fast food" were part of people's lifestyle vocabulary. There simply didn't seem to be enough time to make one's own ice cream; that's if ice cream making ever came to mind at all.

Thankfully, the call of nostalgia and the instinctive longing for a less-complicated lifestyle ushered in the craft age and the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s. People began to yearn for old-fashioned self-sufficiency and a return to basic, simpler pleasures.

Specialty ice cream stores featuring novel frozen treats, and dozens of flavors grew in popularity. They became successful by serving up nostalgic ice cream parlor treats to an entirely new generation of ice cream enthusiasts.

People are more knowledgeable about processed foods today, and there's a strong move to eating organic, all-natural foods. Brands proclaiming "old-fashioned ice cream parlor taste" signify the trend.

Many health-food stores now stock tasty ice creams made with all-natural ingredients for health-conscious consumers who are prepared to pay premium prices, and more people are searching online for ice cream recipes to make healthy frozen desserts.

Yes, homemade is back in style and today's generation is now discovering what our ancestors already knew: Homemade ice cream is the best ice cream!

Ice Cream History Citations

1 - Emy. "L'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces D’Office; ou Les Vrais Principes Pour Congeler Tous Les Raſraichiſſemens." Paris: Chez Le Clerc, 1768.

2 - Ibid.

3 - Ibid.

4 - Raffald, Elizabeth. "The Experienced Engliſh Houſe-Keeper, for the Uſe and Eaſe of Ladies, Houſe-Keepers, Cooks, &c." Manchester: J. Hsarrep, 1769.

5 - Louis Charles (1785–1795), the Dauphin of France and son of Louis XVI and Queen Antoinette, was only 8 years old when he was imprisoned with his parents in Temple Prison in 1793.

After Louis XVI had been beheaded, young Louis Charles was proclaimed Louis XVII, but he was never released from prison. Sadly, he died there of tuberculosis and ill treatment about two years later.

Controversy surrounded the young king's death and after the Revolution some opportunists attempted to assume his identity by claiming that the body autopsied at the prison was not that of Louis Charles.

However, in April 2000 modern DNA tests on tissue from the young boy's mummified heart and a lock of Marie Antoinette's hair confirmed his tragic fate, and his heart received a royal burial in June 2004.

6 - Trotter, Isabella Strange. "First Impressions of the New World on Two Travellers from the Old: In the Autumn of 1858." London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts, 1859.

7 - Hilton, Jeff. (May 17, 2001) "Prelude to Midway—Part II." Jax Air News, Vol. 59, No. 18, pp. 6–8.

8 - The USS Pampanito was the submarine featured in the 1995 screwball comedy "Down Periscope" starring Kelsey Grammer.

Sign Up now for GRANDMA'S DESSERT CLUB and download your FREE PDF COPY of Grandma McIlmoyle's Little Dessert Book. Also receive my regular Bulletin featuring classic recipes and nostalgia.