- Home

- Renaissance Desserts

- Queen Henrietta Maria

Queen Henrietta Maria

Wife of England's King Charles I

Copyright © 2004 by Don Bell

Queen Henrietta Maria of England (1609–1669) was born at the Louvre Palace in Paris on November 4, 1609. Henrietta Maria de Bourbon was the daughter of King Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici, and she was married at the age of fifteen by proxy to England's King Charles I (1600–1649) on May 1, 1625.

The proxy marriage occurred shortly after he was crowned, as she could not be crowned with him due to her adherence to Roman Catholicism. About six weeks later, on June 13th, they were married in person at St. Augustine's Church in Canterbury.

Queen Henrietta Maria's Early Years

Engraved Woodcut of Queen Henrietta Maria

Engraved Woodcut of Queen Henrietta Maria(Source: The Queens Closet Opened)

Queen Henrietta Maria's first four years of marriage was somewhat difficult as Charles largely ignored her. Part of the problem was that she was not his first choice for a wife; he was partial to the daughter of Philip III of Spain, but the marriage had fallen through, and he found Henrietta Maria to be of an opposite temperament to his own.

Also, King Charles was Protestant and Henrietta Maria was devoutly Roman Catholic, and many believed she was ill-chosen to be the queen consort in a Protestant England.

And, maybe most trying, she was not liked or trusted by his closest friend and mentor, George Villiers, the First Duke of Buckingham who would later be immortalized in the Alexandre Dumas novel The Three Musketeers.

Queen Henrietta Maria and King Charles grew much closer after the Duke of Buckingham's assassination in August 1629, and over the years they eventually developed a close bond with each other. They produced nine or ten offspring, six of whom survived into adulthood.

Although Queen Henrietta Maria's grace and affable spirit elicited much loyalty and affection from her household and many of the nobility, those outside her court increasingly viewed her with animosity and suspicion. Her strong devotion to Roman Catholicism and her ongoing communication with the Pope and foreign rulers caused her much alienation.

Not being one to remain in the background, she increasingly involved herself in the affairs of state and diplomacy. Charles openly sought her council throughout his reign and for her part she stalwartly encouraged him to accredit Roman Catholics and to function as absolute ruler in accordance with the divine right of kings, the belief that the monarch's right to rule came from God and not from the people.

Charles acquiesced to Henrietta Maria's use of her foreign contacts in an attempt to gain much needed support during his growing conflicts with Parliament. Although she had been thoroughly devoted to King Charles and her family, Queen Henrietta Maria's frequent communications with the Pope aroused suspicion against Charles; and her close ties with her brother, King Louis XIII of France, a king deeply influenced by his ruthless and politically ambitious chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, served only to foster a particular distrust among his advisors.

The English Civil War

Between 1625 and 1629, unrest grew in response to Charles' heavy-handedness in dissolving three Parliaments, each of which demanded political and religious reforms that he vehemently opposed.

From 1629 to 1640 Charles ruled without Parliament, subjecting the country to unjust taxation and resisting attempts by the Puritans to reform the Church of England; however, when the Scots rebelled against Charles in 1638 for attempting to impose the English Prayer Book on their Presbyterian Church, he was forced to summon Parliament to raise money for a defense.

Parliament, however, refused to vote further taxes until Charles dealt with its demands for reform, and he dismissed Parliament after only three weeks.

In 1640 the Scots invaded northern England forcing Charles to purchase a truce and he had to swallow his pride and recall Parliament to obtain the funds. This Parliament lasted from November 1640 until 1653 and became known as the Long Parliament.

When Roman Catholics in Ireland rebelled in November 1641, Charles petitioned Parliament for support. Parliament refused, not trusting Charles, and quickly passed the "Grand Remonstrance," a detailed attack on many of the king's policies, and pressed for radical reform of the Church of England, including the right to appoint ministers.

Charles was outraged, and in January 1642 he made a disastrous attempt to arrest five leading members of the House of Commons, including Oliver Cromwell, by personally invading the sanctity of the Commons' chamber with armed guards. He was rebuffed and outwitted by clever Parliamentarians and his miscalculated action precipitated the start of the English Civil War later that year.

Meanwhile, Henrietta Maria sailed from Dover in February 1642, ostensibly to deliver her daughter Mary to her new husband, the fifteen-year-old son of Prince Frederick Henry, but her hidden purpose for the journey was to sell her rich trove of jewelery to raise money and arms for her husband's defense.

Accompanying the queen on her mission to the Hague was her most trusted confident, a twenty-three-year-old midget known as Sir Jeffrey Hudson who had with him his mischievous pet monkey, Pug.

Nearly a decade earlier, in 1633, Sir Anthony van Dyck had painted an extraordinary portrait of the then twenty-four-year-old queen. It depicted the beautiful Henrietta Maria and the diminutive court attendant standing on either side of Pug who was balancing on Sir Jeffrey's forearm.

Queen Henrietta Maria

Queen Henrietta Mariawith Sir Jeffrey Hudson and Pug

(Source: Public Domain)

Like those of other artists who painted the queen's likeness, Van Dyck's painting reflects Queen Henrietta Maria's legendary beauty. However, after eleven-year-old Princess Sophia of Bavaria1 first met Henrietta Maria in 1641, she related a curious, and rather unflattering description of her aunt's appearance:

"I was surprised to find that the Queen who looked so fine in [the Van Dyck] painting, was a small woman raised up on her chair, with long skinny arms and teeth like defense works projecting from her mouth..."2

Whether it was simply the capricious perception of a child or the product of a keen eye we'll never really know. Nonetheless, Henrietta Maria's beauty and her devoted companionship thoroughly captivated Charles.

History records the touching scene of the King galloping along the rim of the white cliffs of Dover as he strained to catch a last glimpse of her ship as it disappeared below the horizon bound for Holland.

On encountering a fierce winter's storm during the voyage, Queen Henrietta Maria rallied her ship's officers by spiritedly proclaiming, "Queens of England are never drowned!"

Eventually, Charles was forced to withdraw from London; he maintained control of the king's army and Parliament began raising its own army. The Royalist and Parliamentarian armies clashed several times during that summer and by September full-scale fighting had broken out.

The Royalist forces became known as the Cavaliers (i.e., horsemen or cavalry) and the Parliamentary infantries became known as Roundheads because of their short haircuts.

Though each side could claim supporters of every class, families were often fiercely split in their loyalties. The Cavaliers had a decided advantage in their superior cavalry; however, the Roundheads eventually gained the upper hand owed to their ability to raise money through taxation to better equip their forces.

After spending a year abroad to garner support, Queen Henrietta Maria returned to England in late February 1643, having well accomplished her mission. She had experienced a harrowing crossing, though; besides encountering stormy weather, her small fleet had been pursued by four armed Parliamentary vessels. She debarked at Bridlington in Yorkshire with soldiers and tons of weapons and ammunition.

In a letter to Charles, dated 25th February, 1643, Queen Henrietta Maria described the dangerous unloading of the ammunition ships while being bombarded by cannon fire. The firing became so intense that she eventually fled to the village outskirts and sought shelter crouching down in a ditch:

"Under this shelter we remained two hours, the bullets flying over us, and sometimes covering us with earth … I can say with truth that by land and sea I have been in some danger, but God has preserved me."3

The queen and her forces lay over at York until summertime when some decisive Royalist victories made it safer to advance south to Oxford.

Marching at the head of her army of 4000 heavily armed mercenaries, who she had recruited to fight for the king, and jocularly calling herself "Her She-Majesty, Generalissima," she joined forces with Charles' nephew, Prince Rupert, at Stratford-on-Avon on July 11th; and two days later, on July 13th, she met up with Charles at the battlefield of Edgehill near the fortified city of Oxford.

Fearing the Royalists would unite their forces and lay siege to London, the Parliamentarians signed the Solemn League and Covenant with Scotland that September, and the Scottish forces entered England in January 1644. Blocked by the Parliamentarian forces in the south and attacked by the Scots in the north, the Royalists never succeeded in uniting their forces.

Queen Henrietta Maria remained at Oxford with Charles for nearly nine months, then, pregnant and concerned for the safe delivery of their ninth child, she decided to move to Exeter, leaving her eldest son to remain with the king. Young Charles would eventually flee Oxford in late 1645 and seek exile on the Continent.

When Henrietta Maria had departed for Exeter on April 17, 1644, she did not realize it would be the last time she would ever see her husband, the king.

After the safe delivery of her daughter, Queen Henrietta Maria enjoyed nearly three months of relative safety in Exeter while warmly corresponding with her husband through dispatches. However, by midsummer it became clear that the Parliamentary army was not weakening and she could sense her husband's growing concerns about the war's outcome.

Though outnumbered 3 to 2, the Scottish and Roundhead forces had driven the Royalists into York and on July 2nd Prince Rupert and the Royalists lost the bloodiest battle of the war on Marston Moor. This major Royalist defeat was the result of Cromwell's superior battle strategy and the fiercely committed fighting spirit of his men.

The Battle of Marston Moore is of particular interest to this writer. It happens that my eighth-great grandfather fought the battle on the side of the Royalists.

An old Bell family parchment dating from George III's reign, circa 1775, briefly records my ancestor's experience:

"William Bell, Son of Edwin Bell Esq. of Thirsk, Yeoman born at Thirsk on Saint Thomasday A.D. 1607. Died at Shrovetide A.D. 1686, Aged 79 years. Was with Prince Rupert at the Battle of Marston Moore A.D. 1644. Was wounded. Knowing the country well he fled from the field after the day was lost and was the first person to bring the news to Thirsk that the Royalists were defeated."

For my very existence, I am indeed grateful that William Bell survived! —Don Bell

About a week after the Royalist defeat at Marston Moore, intelligence arrived in Exeter that Parliamentary forces were plotting the queen's capture, so Queen Henrietta Maria fled with her children to Cornwall and sailed from Falmouth harbour on July 14, 1644 to begin her exile in France.

The young queen set up her court at St. Germain near Paris and although she was now nearly impoverished and having to rely heavily on her brother's hospitality, she continued to lobby in vain for Royalist support.

During the winter of 1644–1645, Cromwell purged the high command of the Parliamentarian army and persuaded Parliament to establish a new full-time professional fighting force. The New Model Army with Cromwell as general proved to be undefeatable throughout the summer of 1645; it destroyed the main Royalist field army at the Battle of Naseby on June 14 and the western army at Langport on July 10.

Now, with the realization that he would be unable to hold Oxford and sustain his cause, Charles bid goodbye to his son and sent him to seek exile on the Continent with his mother.

The king left Oxford under a disguise in the following April and by avoiding main roadways and traveling at night, he made his way north to Newark and surrendered to the Scottish army on May 5th.

Though Charles was the son of James VI of Scotland and had inherited his father's throne, the Scots clearly felt no loyalty to him, and they simply viewed this capitulation as an opportunity to advance their own cause.

The End of the Civil War and the Creation of the Commonwealth

The Civil War ended with Charles being turned over to the Parliamentarians by the Scots in January 1647 in return for a large sum of money. He did escape to Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight for a brief period in 1647, where he received support from dissident Scottish nobles; but after a second brief war, which lasted only from April to November, Cromwell's forces recaptured him.

Charles was convicted of treason by a special Parliamentary court and executed on January 30, 1649. The monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished, and England became a republic, called the Commonwealth.

Scotland resented the beheading of Charles, for he had also been styled King of Scotland, and in the months following his execution dissidents plotted an insurrection.

Taking decisive action, Cromwell's army invaded Scotland in July 1650 and defeated the Scottish armies. The rallying Scots then summoned Charles I's eldest son to Edinburgh and crowned him Charles II (1630–1685) at Scone on January 1, 1651.

King Charles II attempted an invasion of England in the summer of 1651, but Cromwell's army soundly defeated him at Worcester on September 3, and he was forced to escape to France about a month later. Scotland was placed under military rule and the English Civil War was finally at an end.

The Protectorate and The Restoration

Unfortunately, the new Commonwealth proved inept at governing and in 1653 a frustrated Cromwell dissolved Parliament with the backing of his militia, and he ruled England as Lord Protector in what amounted to a benevolent dictatorship.

The mantle fell to Cromwell's son, Richard, upon his death in 1658, but it was clear from the start that young Richard did not possess the genius of his father to rule the Protectorate, and he eventually succumbed to a coup.

Parliament was recalled in January 1660, a new Parliament was elected that April, and Charles II was recalled from exile to rule England. He was crowned April 23, 1661, but he first had to assent to the abolition of the feudal rights of knight service, wardship and purveyance, and he acknowledged that he would never rule with the absolute power his father once wielded.

In an act of bitter revenge, Charles II had Oliver Cromwell tried posthumously for treason and sentenced him to be drawn and quartered. And although Cromwell had died of natural causes and was buried in 1658, his body was exhumed by royal decree and hung from a gallows by chains for several days on public display; it was then beheaded, but it was not quartered and dispersed, likely because of its state of decay; it was simply reburied in its original coffin in unconsecrated ground.

With the Restoration of the monarchy and her eldest son now on the throne, Queen Henrietta Maria returned briefly to England in October 1660, and she later made a second more-lengthy visit in 1662. After securing a generous pension from Parliament, she returned to France in 1665 and founded a convent at Chaillot.

Queen Henrietta Maria died at age 60 on August 31, 1669 while residing at Château de Colombes. She was later buried at the Cathedral of St. Denis in Paris.

She did not enjoy an easy life in many respects, but she lived to see her son Charles resume the throne of England, and she would have been pleased to see his younger brother convert to Roman Catholicism in 1671, and succeeding his brother in 1685, become King James II (1633–1701).

The Legacy of Queen Henrietta Maria

HM Queen Henrietta Maria4

HM Queen Henrietta Maria4With the passage of time people's harsh memories faded, and forgiveness brushed aside any of the resentments and suspicions once held towards Queen Henrietta Maria.

After Charles II had secured the throne, many English sympathized with the former plight of the beautiful queen and they celebrated her dauntless courage. Paintings, song and verse romanticized her flight into exile and her untiring efforts to secure the throne for her husband and her sons.

Two centuries later, in 1881,

writer and poet Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) gave worded expression to her

difficult life and her unflinching devotion in the plaintive verses of a poem.

Queen Henrietta Maria

In the lone tent, waiting for victory,

She stands with eyes marred by the mists of pain,

Like some wan lily overdrenched with rain:

The clamorous clang of arms, the ensanguined sky,

War's ruin, and the wreck of chivalry,

To her proud soul no common fear can bring:

Bravely she tarrieth for her Lord the King,

Her soul a-flame with passionate ecstasy.

O Hair of Gold! O Crimson Lips! O Face

Made for the luring and the love of man!

With thee I do forget the toil and stress,

The loveless road that knows no resting place,

Time's straitened pulse, the soul's dread weariness,

My freedom and my life republican!5 —Oscar Wilde

Some readers may not be aware that Queen Henrietta Maria's name became immortalized in North America. Not only can Cape Henrietta Maria be found on the west coast of Canada's James Bay, but in 1632 Charles I granted a large tract of land to George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore.

Calvert died soon after, and the king then granted the region to his son, Cecilius Calvert (1605–1675), the second Lord Baltimore. Charles I named the region Terra Maria, or Maryland, in honor of his wife.

The first party of English colonists to Maryland arrived in 1634 led by Cecilius Calvert's brother, Leonard Calvert, later to be appointed governor. They established a colony in a broad meadow on the western shore of the Potomac River, which they named St. Mary's City.

Lord Baltimore was a devout Roman Catholic who strongly believed in religious freedom and welcomed settlers of all faiths. He drafted a law to grant religious freedom to all residents in the colony. Maryland's Assembly passed it in 1649, and it became the first statute to grant religious freedom in the American Colonies.

The State of Maryland takes great pride in its long-standing reputation for religious tolerance and in its deep British roots. The great seal of Maryland features a dashing Lord Baltimore astride a charging horse, and it somehow seems fitting that the official state sport is jousting.

Maryland's name and heritage continue to preserve the memory of Queen Henrietta Maria.

The Queen's Recipe Collection

A lesser-known part of Queen Henrietta Maria's legacy is a fascinating collection of recipes published in 1658 by her former servant known only as W.M.

Did the queen have a passion for sweetmeats? We cannot know for sure, but if we are willing to accept the testimony W. M. that "The Queens Closet Opened" discloses Queen Henrietta Maria's personal recipe collection, we find that many recipes are for "Preſerving" and "Candying" sweetmeats.6

Indeed, we know that confectionery was prominent at royal entertainments and if we consider that she always delighted in attending banquets and balls, it would not be reasonless to conclude that Queen Henrietta Maria did enjoy eating confections.

It's alleged that her husband, Charles I, once hired a French chef named De Mirco to make ice cream as a frozen pie for a royal banquet. It was so well-received legend has it that he commanded the chef to keep the recipe a secret, and he paid him a yearly retainer of £500 to ensure his silence.

It's also known that Charles II enjoyed eating ice cream throughout his nine-year exile in France and that after the Restoration he had ice cream and white strawberries served at a banquet for the Feast of St. George at Windsor Castle in 1671.

So, it's not unreasonable to assume that where there was ice cream there was an abundance of sweetmeats also.

Interestingly, among Henrietta Maria's collection of recipes can be found instructions for writing "Letters of Secrets" using a solution of powdered alum in water.

To write Letters of ſecrets that they cannot be read without the directions following.

Take fine Allum, beat it ſmall, and put a reaſonable quantity of it into water, then write with the ſaid water. The work cannot be read but by ſteeping your paper into fair running water. You may likewiſe, write with Vinegar, or the juyce of Lemon or Onion; if you would read the ſame, you muſt hold it before the fire.7

It's more than tempting to imagine that such a simple, yet effective technique of secret writing was used by Queen Henrietta Maria to covertly correspond with her husband when they became separated during the English Civil War, and she was in France.

Anyway, it's a romantic thought. Henrietta Maria's recipe collection could never be thought dull.

Henrietta Maria Immortalized in Film

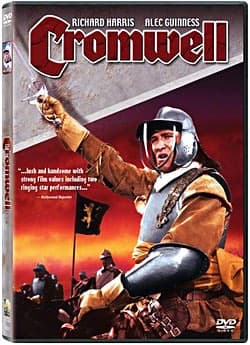

1977 Cromwell Movie

1977 Cromwell Movie(Source: Fair Use)

In 1977, Columbia Pictures made a major motion picture depicting the tumultuous years of the English Civil War up to the establishment of the Protectorate.

The movie titled "Cromwell" was produced by Irving Allen and starred Richard Harris as Oliver Cromwell, Alec Guinness as King Charles I, and Dorothy Tutin as Queen Henrietta Maria.

The historical epic's eye-filling on-location cinematography, the period costuming, the brilliant portrayal of the court intrigues, and the gripping battle sequences bring Henrietta Maria's England alive.

The film is well worth a view while munching on a plate of chewy candy (suckets) made using Queen Henrietta Maria's favorite dessert recipes.

Several of Henrietta Maria's royal recipes for cake, candy, marchpane, marmalade, and fruit pastes are featured in the Renaissance Dessert Recipes section on this site.

Endnotes

1 Sophia of Bavaria (1630–1714) was the youngest daughter of King Frederick V of Bavaria and Elizabeth Stuart, the eldest daughter of James I and sister to Charles I; Henrietta Maria became Elizabeth Stuart's sister-in-law after marrying Charles I.

In 1658 Princess Sophia married Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg, and Elector of Hanover. On May 28, 1660 she gave birth to George Lewis who would later be crowned King George I of England.

2 "Painting In Britain: 1530-1790" by Ellis Waterhouse, 5th Edition, pg. 74, published by Yale University Press, 1994.

3 "History And Topography Of The City Of York;..." Vol. 1, pp. 238-239, by J. J. Sheahan and T. Whellan, published by Beverley: Printed for the publishers by John Green, Market Place, 1857.

4 Photograph by Franz Hanfstaengl of Van Dyck's portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria, published in John Morley's "Oliver Cromwell." New York: The Century Company, 1900.

5 Wilde, Oscar. "Poems." Boston: Robert Brothers, 1881.

6 "The Queens Closet Opened: Incomparable Secrets in Phyſick, Chyrurgery, Preſerving, Candying, and Cookery" by W. M., published by Nathaniel Brooks, London, at the Angel in Cornhill, in 1658.

7 Ibid.

Sign Up now for GRANDMA'S DESSERT CLUB and download your FREE PDF COPY of Grandma McIlmoyle's Little Dessert Book. Also receive my regular Bulletin featuring classic recipes and nostalgia.